There Is No Demos without a Crowned Monos

Mick Hume, chief editor of The European Conservative, has been very much exercised recently over the restoration of the unique identity of Europe’s nations, as opposed to their absorption into a bland, borderless, tradition-hating European superstate. That is to his credit, but it is unhelpful that he links this project with an ideological faith in democracy:

‘Amid all the confusion and uncertainty about Donald Trump, trade tariffs, and the prospects for peace in Ukraine, one thing should be clear: the “End of History” dreamworld of the globalist elites is itself coming to an end. Their fantasy of a peaceful, prosperous borderless world order run by bureaucrats and bankers has been brutally exposed.

‘Instead we live, as I wrote here last month, in “a new world of nation states.” Democratic nations now have to wake up and defend the interests of their people in turbulent times’ (‘Nationalism Should No Longer Be a Dirty Word,’ europeanconservative.com).

He is not wrong when he says, ‘The anti-nationalism and anti-populism of the EU elites is all about their fear and loathing of the demos.’

But the hatred of the liberal/globalist oligarchs for the people and their age-old, ‘regressive’ customs and traditions, and their efforts to obliterate the latter, are not overcome simply by implementing democratic government, something he implies when he states,

‘A revived attachment to the nation can offer a safe home for the masses cut adrift from their roots by the politics of the globalist elites. More than that, national consciousness and the defence of national sovereignty give people the chance to take democratic control of their destiny.

‘The nation-state, let us always remember, is the only model on which democracy has been proven to work; any talk of “Europe-wide democracy” or “global democracy” is merely a cover for rule by the unrepresentative bureaucracies of the United Nations, World Health Organisation or European Commission.’

For, echoing St Gregory the Theologian (+4th century), government by a multiplicity of people, whether the many (democracy) or by the few (aristocracy), necessarily creates disharmony, which ‘is the first step to dissolution’ (Oration XXIX, II).

There are ways to manage this disharmony, to make it less damaging to the nation. One of Dixie’s best statesmen, John C. Calhoun, recommended the concurrent majority, allowing each of the distinct interest groups in a country to have both representation and veto power within the government, as a means to protect minorities from encroachments by the majority and to encourage unanimity in decision-making, so that the common good can be served:

‘Calhoun’s political concepts are still relevant. By creating a foundation for theories such as concurrent majority or nullification, Calhoun points to solutions. On the issue of the fundamental role of the veto, Calhoun seemed to be principled. As historian Charles M. Wiltse says: The concurrent majority is the negative of each interest on all the others – call it veto, check, nullification, or what you will – that makes possible resistance to the abuse of power. Without an effective negative, and this is the only effective one, there can be no constitution at all’ (Karol Mazur, ‘Calhoun’s Lesson for Europe,’ abbevilleinstitute.org).

We certainly agree with that. But we also urge caution. For this is the danger of our time, is it not? – to believe that some act of government, some constitutional change or some law, or some scientific advancement – something external to man – will solve our most pressing problems, whether Mr Hume’s democracy, Calhoun’s concurrent majority, and so forth and so along.

It is not so. National healing, reform, etc., have much more to do with man’s internal life than with his external conditions. The latter do matter, but not to the degree that we are led to believe they do. The spiritual, the theological, must therefore be addressed as well.

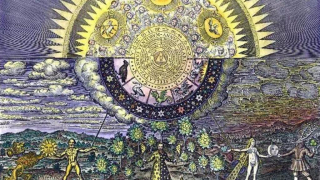

We made a small step in that direction with St Gregory’s Oration. We will now continue in that vein. St Gregory follows the quotation given above by stating the Orthodox Church’s preference for monarchy (he is speaking about relations within the Godhead, but they are just as applicable to mankind, for we are made in the image and likeness of God). Rule by a single will promotes unity; it keeps discord from bringing the nation to ruin. There will always be a multitude of cities, corporations, families, etc., in any given country, but the king helps harmonize those many voices.

Furthermore, monarchy is one of the keys to the continued existence of the demos/ethnos. The king is an icon of the people, the living image of all their traditions and all their history. If he disappears, their identity is struck a terrible blow. An example:

‘But by 553, Ostrogothic kingship was ended. The disappearance of the Ostrogoths as a people soon afterwards offers the most dramatic example of the dependence of a people in the early Middle Ages upon kingship for their tribal identity:

‘“The Gothic tribal name vanished in Italy after the loss of the kingship to the extent that only research carried out in the most recent times has been able to establish that the Goths did not emigrate but rather were assimilated’” (Henry Myers, Medieval Kingship, Nelson-Hall, Chicago, Ill., 1982, p. 77).

Political philosopher Alexander Dugin goes into more detail about the role of quasi-religious rulers like kings within the ethnos:

‘The shaman stands at the center of the ethnos and is its principal “mask,” “the mask of masks.” The shaman is the personification and functional synthesis of the ethnos. He fulfills the ethnos’ main task: he takes care to preserve the constancy of the ethnic structure. The shaman expresses balance, that which makes the ethnos an ethnos—invariability, continuity, the translation of the code, the transmission of knowledge (myths, rites, traditions) and the correction of the ethnos’ social and natural faults. The shaman ensures the invariability of the stasis. He is the expression of the ethnos as a static phenomenon’ (Ethnos and Society, Michael Millerman translator, Arktos, London, 2018, p. 33).

More important even than kingship to maintaining the national identity is the Christian Faith. Even in the absence of their kings, many Orthodox countries were able to maintain their identity because they knew that their national life was inseparable from their life in the Orthodox Church. Such were Greece, Serbia, etc., under the Turks, and Russia, Romania, etc., under the communists, and so on.

But the king has also been a benefactor of the Church:

‘In a rather typical treatment of kingship for the later Carolingian period, Cathwulf . . . refers to the ruler as God’s regent or vicar in the limited context of having responsibility on earth for the enforcement of God’s laws and the advancement of the Church’ (Myers, p. 139).

Bishop Jonas of Orleans (d. 843), likewise wrote,

‘It is the particular function of the king to govern God’s people, to rule with equity and justice, and to try hard to ensure peace and harmony. First of all, he should be the defender of the churches and the clergy . . . . With arms and through the Church of Christ he should assure the protection of widows, orphans, other poor persons, and each and all that lack the means to defend themselves. . . . He is to know that it is God’s doing and not man’s which has committed these responsibilities to him’ (Ibid.).

Thus, the king, the crowned monos (Greek word meaning roughly single, alone, or solitary), in his own person, and much more by promoting Christianity amongst his people, is essential to maintaining and strengthening the unique cultural identity of the ethnos/demos.

The problem we run into today is that, of the kings who are still upon their thrones in Europe, most of them act nothing like the good Christian kings of the past, whose characteristics have just been described and whose lives are recorded in books like Fr James Thornton’s Pious Kings and Right-Believing Queens, on various web sites, and so on. The solution, therefore, of too many conservatives like Mr Hume is to seek salvation in a secular populist democracy, in the more or less direct rule of the people/demos. This is a better option at present than the utterly abominable rule of the current degenerate oligarchy in Europe, but in the long run the nations that adopt this solution will be torn apart by the passions of the demos/ethnos, just like every other democratic country unrestrained by a father-king, without the balance provided by polycentric centers of power and some kind of system of concurrent majority for them to live within, and untransformed by the Grace of the All-Holy Trinity.

Yet, as we said, Mr Hume does not countenance these things in his essay:

‘Conservatives should not only embrace the populist revolt as the best hope of shaping Europe’s future. They should also fight to give populism a positive political story, by insisting that patriotism is not the plaything of the polite classes, and that nationalism should no longer be considered a dirty word.’

Baptism of the demos in the Orthodox Church, she who has not adulterated the Apostolic teaching with innovations like the Roman Catholics, Protestants, etc., is the best hope of shaping Europe’s future, and corporatist monarchy already has an impressively positive political story to tell, much better than the unending strife and envy and wars, with their tens of millions of deaths, of the ‘democratic’ 18th-21st centuries. These are the things that must be advanced if Europe and all the West want a good, vibrant future.

The reality of this is already making itself known, and will continue to do so, but are there enough people with the wisdom and virtue to see and understand it, and to act accordingly?