AI and the Inhuman Modern State

The French mystical writer Simone Weil (d. 1943) warned in the 20th century about the cold, soulless, mechanical nature of government that had come into existence:

‘The State is a cold concern which cannot inspire love, but itself kills, suppresses everything that might be loved; so one is forced to love it, because there is nothing else. That is the moral torment to which all of us today are exposed.

‘Here lies perhaps the true cause of that phenomenon of the leader which has sprung up everywhere nowadays and surprises so many people. Just now, there is in all countries, in all movements, a man who is the personal magnet for all loyalties. Being compelled to embrace the cold, metallic surface of the State has made people, by contrast, hunger for something to love which is made of flesh and blood. This phenomenon shows no signs of disappearing, and, however disastrous the consequences have been so far, it may still have some very unpleasant surprises in store for us; for the art, so well known in Hollywood, of manufacturing stars out of any sort of human material, gives any sort of person the opportunity of presenting himself for the adoration of the masses’ (The Need for Roots, Arthur Wills translator, Routledge Classics, New York, 2003, p. 114).

She saw more keenly than she realized. For it is no longer simply the case that ideologically driven revolutionaries; heartless bureaucrats; greedy oligarchs; etc., who are bereft of the warmth of Christian love and kindness, have taken over the offices of government and wield its power. Now we are witnessing the transformation of the State into an actual machine, as AI is becoming an integral component of the governing system:

‘Artificial intelligence (AI) is writing law today. This has required no changes in legislative procedure or the rules of legislative bodies—all it takes is one legislator, or legislative assistant, to use generative AI in the process of drafting a bill.

‘In fact, the use of AI by legislators is only likely to become more prevalent. There are currently projects in the U.S. House, U.S. Senate, and legislatures around the world to trial the use of AI in various ways: searching databases, drafting text, summarizing meetings, performing policy research and analysis, and more. A Brazilian municipality passed the first known AI-written law in 2023’ (Nathan Sanders, Bruce Schneier, lawfaremedia.org; many thanks to Dr Joseph Farrell for mentioning this article at his web site).

The authors explain why legislators are likely to adopt AI in their task of writing laws:

‘Congress may or may not be up to the challenge of putting more policy details into law, but the external forces outlined above—lobbyists, the judiciary, and an increasingly divided and polarized government—are pushing them to do so. When Congress does take on the task of writing complex legislation, it’s quite likely it will turn to AI for help.

‘Two particular AI capabilities enable Congress to write laws different from laws humans tend to write. One, AI models have an enormous scope of expertise, whereas people have only a handful of specializations. Large language models (LLMs) like the one powering ChatGPT can generate legislative text on funding specialty crop harvesting mechanization equally as well as material on energy efficiency standards for street lighting. This enables a legislator to address more topics simultaneously. Two, AI models have the sophistication to work with a higher degree of complexity than people can. Modern LLM systems can instantaneously perform several simultaneous multistep reasoning tasks using information from thousands of pages of documents. This enables a legislator to fill in more baroque detail on any given topic.

‘ . . . AI can be used in each step of lawmaking, and this will bring various benefits to policymakers. It could let them work on more policies—more bills—at the same time, add more detail and specificity to each bill, or interpret and incorporate more feedback from constituents and outside groups. The addition of a single AI tool to a legislative office may have an impact similar to adding several people to their staff, but with far lower cost.

‘ . . . There’s more that AI can do in the legislative process. AI can summarize bills and answer questions about their provisions. It can highlight aspects of a bill that align with, or are contrary to, different political points of view. We can even imagine a future in which AI can be used to simulate a new law and determine whether or not it would be effective, or what the side effects would be. This means that beyond writing them, AI could help lawmakers understand laws. Congress is notorious for producing bills hundreds of pages long, and many other countries sometimes have similarly massive omnibus bills that address many issues at once. It’s impossible for any one person to understand how each of these bills’ provisions would work. Many legislatures employ human analysis in budget or fiscal offices that analyze these bills and offer reports. AI could do this kind of work at greater speed and scale, so legislators could easily query an AI tool about how a particular bill would affect their district or areas of concern.’

We then come to an important part of the authors’ essay – why this new development in governance is necessary at all:

‘We should understand the idea of AI-augmented lawmaking contextualized within the longer history of legislative technologies. To serve society at modern scales, we’ve had to come a long way from the Athenian ideals of direct democracy and sortition. Democracy no longer involves just one person and one vote to decide a policy. It involves hundreds of thousands of constituents electing one representative, who is augmented by a staff as well as subsidized by lobbyists, and who implements policy through a vast administrative state coordinated by digital technologies. Using AI to help those representatives specify and refine their policy ideas is part of a long history of transformation.’

In other words, because society and government have become as complex as they have, lawmakers are required to use AI simply to fulfil their duties in the new, convoluted techscape.

But this begs the question: Is all of this complexity necessary? Is it beneficial?

It would seem not. Just a glance at the toll that internet message boards, social media, and similar things have had on people, particularly the young – how they encourage the mutilation of language along with insults, bullying, impoliteness, addiction, murder, suicide, and any number of other evils – is proof enough that at least some of what modernity’s unholy trinity of science-technology-industry (to use the Southern Agrarian Wendell Berry’s words) has wrought ought to be rejected.

Miss Weil’s description of factory life is also worthy of consideration in this context:

‘The child while at school, whether a good or bad pupil, was a being whose existence was recognized, whose development was a matter of concern, whose best motives were appealed to. From one day to the next [in the factory—W.G.], he finds himself an extra cog in a machine, rather less than a thing, and nobody cares any more whether he obeys from the lowest motives or not, provided he obeys. The majority of workmen have at any rate at this stage of their lives experienced the sensation of no longer existing, accompanied by a sort of inner vertigo, such as intellectuals and bourgeois, even in their greatest sufferings, have very rarely had the opportunity of knowing. This first shock, received at so early an age, often leaves an indelible mark. It can rule out all love of work once and for all’ (Need for Roots, p. 54).

It is thus no bewildering wonder to observe what Miss Weil spoke of at the outset of this essay: the increasing hunger of the masses of people living under the conditions described to receive some slight recognition of their humanity by a man of high position, in return for which they become his most loyal supporters and followers. Unfortunately, it is likewise true what she said afterwards, that many of them are shallow show-business bozos, like Trump, Newsom, Zelensky, Clinton, etc.

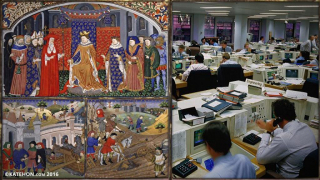

And yet in this reaction there is hope, for it could be the first steps toward the restoration of Christian monarchy, that primordial form of government reflective of the rule of the cosmos by God the All-Holy Trinity. The advantages of this for the post-Great Schism West (whether her Roman Catholic, Protestant, or secular Enlightenment populations), dominated as she is by notions of the rule of an impersonal law, are explained by Dr Matthew Raphael Johnson:

‘The notion of law here is also significant. Liberal democracy means that the “rule of law” dominates. This is another way of saying that whoever the oligarchy is capable of financing to electoral victory will make the laws in its favor. . . .

‘The idea of the law being “wooden” is the object of the criticism of the Slavophiles . . . , to wit, that the law, without the power of mercy behind it, becomes an alien force, an imposition. . . . [Law in the West] is the product of moneyed interests who actually write the law, and faceless staffers and judicial clerks who write the actual text. For traditional and Christian societies, the law is manifested in the historical institution of the monarch, who can overthrow the law temporarily for hard cases and for the sake of mercy. . . . For example, it was common in Orthodox Byzantium and Russia, every few years or so, to cancel the collection of back taxes and even order the cancellation of private debts. This was done for specific religious holidays, the ascension of a new monarch, victory in battle or just because the state was no longer able to afford the collection process. This, of course, is contrary to the rule of law. In modern oligarchical societies, the cancellation of private or public debt, for any reason, is unthinkable.

‘ . . . Russian Tsars heard hundreds of such petitions [appealing the rulings of the judiciary] weekly, and the decision was based on the common good of the ethno-nation, deriving from a royal authority that was beholden to no moneyed interest, rather than a modern judiciary that is largely the product of political spoils’ (The Third Rome, 3rd edition, The Barnes Review, Washington, D. C., 2010, pgs. 166-7).

Tellingly, it is admitted that these same oligarchical special interests are the ones building the AI systems that will be writing laws in the future:

‘There are real risks to AI-written law, but those risks are not dramatically different from what we endure today. AI-written law trying to optimize for certain policy outcomes may get it wrong (just as many human-written laws are misguided). AI-written law may be manipulated to benefit one constituency over others, by the tech companies that develop the AI, or by the legislators who apply it, just as human lobbyists steer policy to benefit their clients’ (Sanders and Schneier).

It is well that, in addition to the kings, there are more authorities that the Christian peoples of the world have turned, and may still turn, for mediation in the realm of politics. Often it has been the Orthodox saints, whether West or East, they sought for resolution of disputes:

‘As in Uzalis, so at Minorca, [Saint] Stephen, by resolving the tensions between intertwined and potentially conflicting structures of power, had emerged as the patronus communis, “the patron of all.”

‘It is in this way that little communities for whom the structure of the Roman Empire either meant little, or had ceased to exist, grappled with the facts of local power in a changing world. The praesentia of the saints had been made available to them in gestures that condensed the poignant yearning for concord and solidarity among the elites of the Western provinces in its last century; yet, once available, the imaginative dialectic that surrounded the person of the saint insured that the shrine would be more than a reminder of the ideal unity of a former age: the shrine became a fixed point where the solemn, necessary play of “clean power”—of potentia exercised as it should be—could be played out in acts of healing, exorcism and rough justice’ (Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity, U of Chicago Press, Chicago, Ill., 1982, p. 105).

Not all democratic systems are evil in themselves. Yet Western liberal parliamentarism is approaching what seems to have been its telos all along: a tool of oligarchs to control government and the ethnos through the illusion of elections and the sovereignty of the people. The emergence of AI that will perform the essential function of members of parliament, i.e., writing laws, with more governmental tasks envisioned for it, like judgeships – such things will only further dehumanize the state apparatus that the oligarchic eradication of authentic culture, for the sake of greater control, more money, and other acts of exploitation, inaugurated centuries ago.

Advanced technology, rather than liberating people, is placing upon them a yoke of slavery heavier than anything their pre-Modern ancestors ever knew.