Beauty has become fashionable ugliness

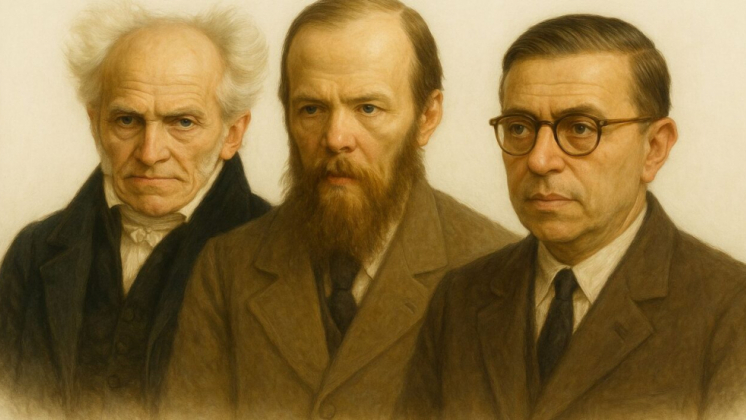

We live in ugliness and brutality. Beauty has become fashionable ugliness. The phrase is by Jean Cau, written half a century ago at the dawn of degradation in a brilliant essay that is misunderstood despite (or because of) its value, The Stables of the West. Cau, author of The Knight, Death and the Devil, an allegory on existence based on the engraving of the same name by Albrecht Dürer, was in his youth secretary to the worst of the French bad masters, Jean Paul Sartre, only to radically distance himself from him and end up ostracised by the cultural mafias.

We live surrounded and pursued by ugliness: in cities, in the disfigured landscapes that surround even commodified icons of art such as Florence and Siena, in ethics, in personal aesthetics. The way our contemporaries behave, speak and even stand is ugly, with their sunken chests, hunched over artificial devices, dressed in hideous rags, hoodies emblazoned with empty phrases strictly in English and iconography with infernal references, trousers that are deliberately torn and frayed (they cost more and fools fall for it), dishevelled hair with unnatural colours – purple, green and blue dominate – and, of course, the obligatory tattoos, generally ugly, shapeless or repetitive (where is the coveted individualisation?). Scribbles symbolising nothingness, the overwhelming force of fashion or the anxiety-inducing desire to make the body a unique “work of art”.

Few seem to notice or care about the ugliness: it is part of normality and, if it is fashionable, it is defined as beauty. A chamber pot as a headdress would become beautiful if the Pavlovian reflex of the trend imposed it on the human herd. Ugliness is democratic, in the sense that it is material, immediate and accessible to all. Beauty is aristocratic in that it elevates, makes us reflect, brings inner joy, stimulates reflection and projects us into the realm of the soul. Yet beauty – in art, song, dance, gestures, attitude, nature, in everything that surrounds us – has always been perceived by human beings as superior, giving meaning to life. When faced with the spectacle of beauty, we feel an inner stirring, an often inexplicable emotion and emotion, we experience a flash of eternity.

But we live in the most narrow-minded and materialistic time in history, so the question is: what is beauty for? We do not know the answer; we turn to the giants on whose shoulders we scrutinise the world. For Aristotle, beauty is a gift from God. Since we have become atheists, here is a strong argument in favour of ugliness. Shakespeare has one of his characters say, “Beauty alone is enough to persuade the eyes of men, without the need for orators”. But we are blind led by madmen, another pearl from the English bard. Nothing that is beautiful is indispensable to life. The only thing that is truly beautiful is that which serves no purpose. Everything that is useful is ugly. So says Théophile Gautier in Mademoiselle de Maupin. A blooming rose serves no purpose, nor is the enchantment of a sunset or the song of a bird useful to anyone. Better the weather forecast or the sound of the cash register. Only what is useful is useful, and ugly are the faces of power, the faces of courtiers or department heads, as amiable as the salesperson eager to foist a pair of shoes on us.

We cannot say how beauty will save the world—the powerful exclamation of Dostoevsky's Prince Myshkin—but we are certain that ugliness destroys it. This is clear to those who still look, as well as see. Instead, kitsch predominates – that which is excessive, a crude imitation of beauty – along with rampant sloppiness, starting with flat language reduced to a few words, stereotypical phrases, onomatopoeia, and foul language turned into filler words. Disorder and formlessness prevail, passed off as immediacy. The noble soul, said Goethe, aspires to order and law, whose relationship with beauty it intuits. Even clearer were the Greeks, for whom the good and the beautiful tend to coincide (kalòs kài agathòs) on the path to virtue. Beauty is truth, and truth is beauty, is the cry that bursts from the mouth of John Keats, the Romantic poet, before a Greek urn. Therefore, ugliness is a lie: in fact, we live immersed in lies, believed because of the power of those who tell them and the ineptitude of those who listen to them, no longer trained by and in the beauty of truth.

Any creative expression (which is something else) is defined as art, however bizarre, instrumental, obscene or ridiculous. They have found a synonym: installation. They pass off a banana hanging on the wall with adhesive tape as art. More honest is Andy Warhol's serial advertisement for Campbell's tomato soup, displayed as in a supermarket, which elevates the commodity form to art, the mission of pop. Or to reduce art to a consumer product in a world dominated by the false messages of propaganda and advertising, the consumer-friendly new sciences. The figurative arts have ceased to represent man, turning not to nature but to the formless, the abstract, and not infrequently to the senseless. The ideal form of non-art is the rhizome, the excrescence that overflows without direction.

A caste of self-styled experts decides what we should consider art and sets its price in cash. If everything has a price, nothing has value. Beauty is the temple of the spirit of the creature that looks up. Like the religious temple, it is sacred because it is not for sale. Unthinkable where everything is valued in money. I have a coat worth a thousand euros, I bought a car for fifty thousand, a Van Gogh painting is worth a hundred million dollars. His painting A Pair of Shoes, much loved by Picasso, is so expensive partly because it was the subject of Martin Heidegger's intense reflection on the genesis of the work of art. Poor Vincent, that's what philosophy is for, a typical question asked by fools.

As for music, is the rhythmic noise, amplified by artificial mechanisms, of most rap and trap music, accompanied by insane, vulgar or violent lyrics, art? Or the deafening, mind-altering sounds of rave parties, whose purpose is to remove inhibitions to the point of excess in drugs, alcohol and sex, or the confused happening, the monotonous circle dance of hysterical, soulless dervishes who call it freedom. Art has expelled man from its horizon, now made up of mass-produced products, as Walter Benjamin foresaw in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, or rather by a pseudo-art that “chuckles, mocks, corrodes and destroys everything” (J. Cau).

Ugliness and brutality are signs of the times, the fruits of a dominant, destructive, soulless will, the source of a desperate nihilism. Political ugliness is also on the rise, the soulless management of cold technocrats with no plan other than personal success. And there is economic and social ugliness, which calls the domination of a few giants who drive out their competitors one by one the free market. And there is ethical ugliness in the constant competition, the war of all against all that is liberalism. As for aesthetic ugliness, how can we judge the stains and squiggles passed off as street art that deface walls, buildings and means of transport, in which Bansky, the pseudonym of the unknown writer and icon of street art, has no part? Ugliness is the non-places - airports, stations, junctions, entrances and forecourts of shopping centres - where the traveller, reduced to a hamster in a wheel, is forced to wander. Ugliness is the obsessive search for pleasure for its own sake, without face or purpose. And the crisis of civilisation has become a “fearful rejection of all heights” (The Knight, Death and the Devil) of the postmodern crowd whose aesthetic code is kitsch. After all, the bourgeoisie has never possessed taste, except for mimicry, imitation of what was higher.

Horrendous is the ugliness combined with the brutality of the rainbow iconography of gay pride, the disguise that alludes to evil and sinks into the obscene. It has nothing to do with the composed dignity of the Fourth Estate, the workers and peasants, simple, beautiful and elegant as they burst into history in Pellizza da Volpedo's painting. Today, bodies disfigured by hatred, purple with rage, devoid of the decorum of yesterday's struggling proletarian crowds, roam around. From the Fourth Estate, we have moved on to the masses, then to the people, ending up in a directionless swarm. We live in a present devoid of self-awareness, characterised by an obsessive rejection of “before” combined with indifference to “after”. Nothing like Goethe's invocation “Stay, moment, you are so beautiful!”. The beauty of the unrepeatable moment often lies in the dazzling vision of beauty, in its contemplation and ineffability, in the surprise that springs from the heart. However, one must have a heart – distinct from the beating muscle – in order to draw on the wonder of beauty, inaccessible to the “last men” who sneer and snicker, who do not know how to despise themselves, incapable of giving birth to stars because they are insensitive to beauty.

This is how they wanted us to be, this is how they are shaping us with a success that leads to pessimism. All that remains is to think the opposite of the prevailing opinion, to let out a cry among the ruins. Ugliness becomes fashionable normality for those who can no longer see the ruins that surround them. Nor, like Saint Exupéry's Pilot of War, can they guess that among the crumbled stones in the realm of quantity, the foundations of new cathedrals can be glimpsed - to be rebuilt. These were not built by the tourist board. To raise them, it took much more than an opinion; it took faith, a lofty goal. And an idea of beauty that lifts the gaze to the sky and disregards the clamour below. One cannot be against the wolves and be part of the pack.

https://www.ereticamente.net/la-bellezza-e-diventata-la-bruttezza-alla-moda-roberto-pecchioli/

Translation by Costantino Ceoldo